142 | Business World Magazine |

October 2013

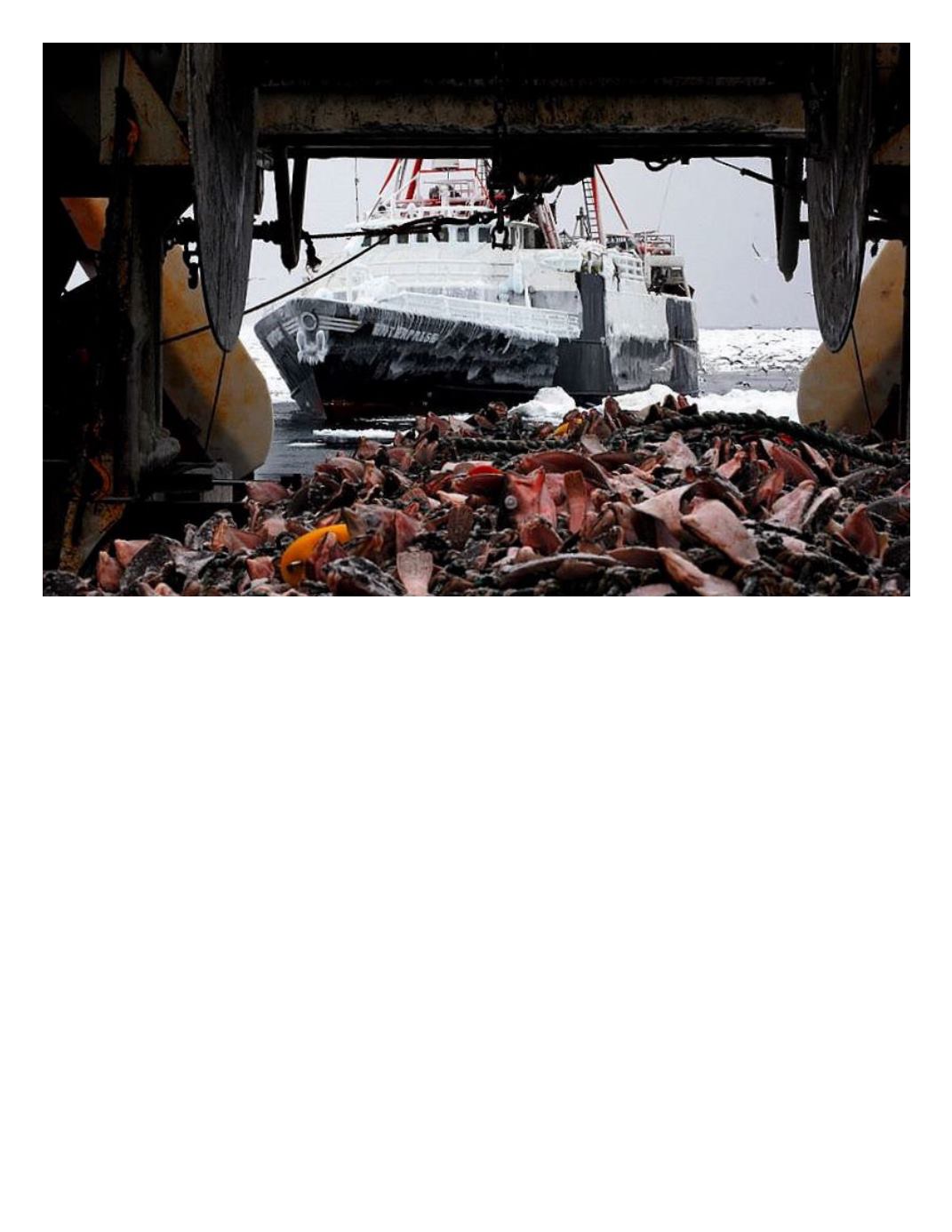

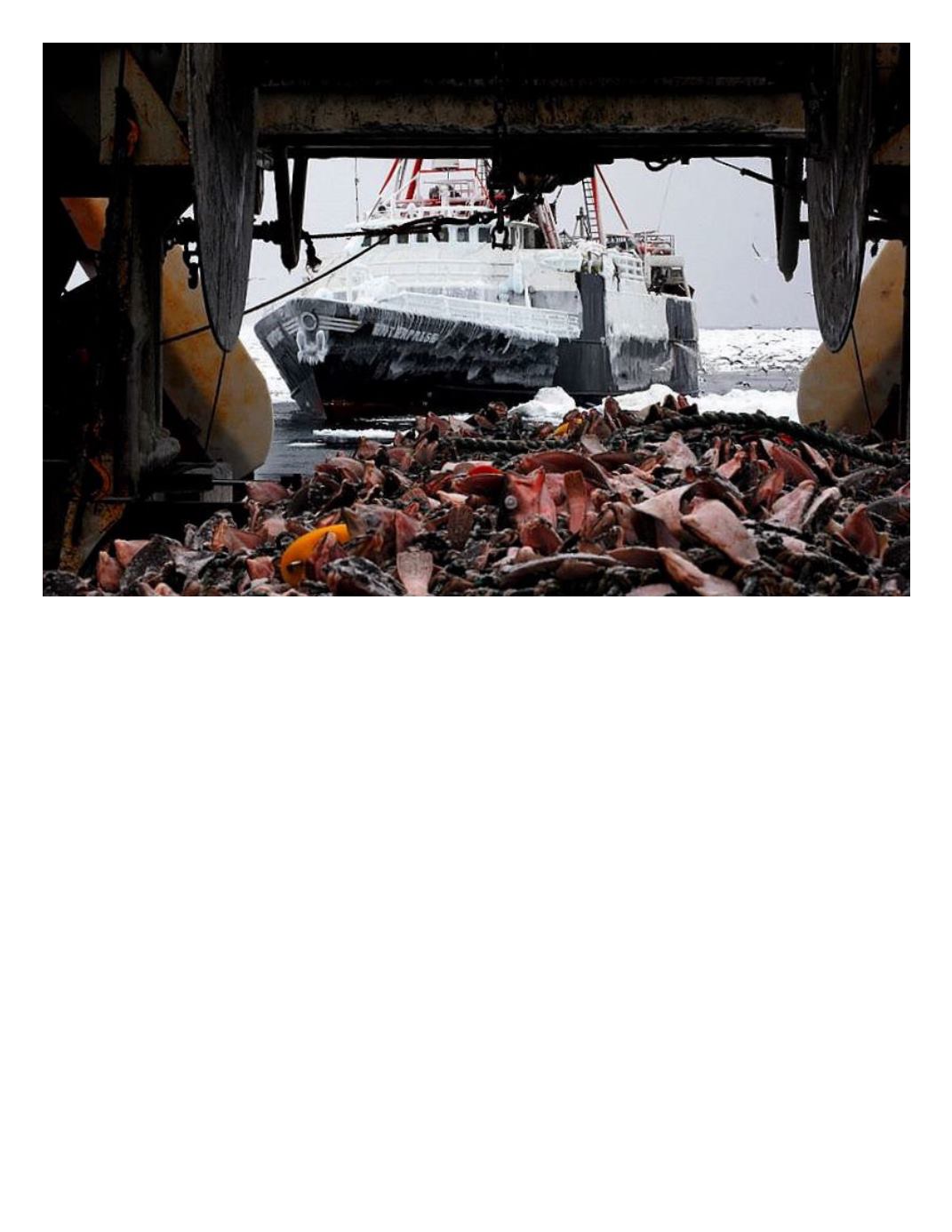

cies, as prohibited species were allocated

to other target fisheries. In the course of

fishing, the fishery might avoid capture of

other species, but some are always caught

(known as bycatch) which are required to

be discarded. And upon reaching quota

with respect to the species allocation or

prohibited species catch limits, the fishing

operations were brought to an immediate

halt. It basically fostered a lot of compe-

tition and resulted in significant impact

to species that were ultimately cast away

when not part of the allocated species.

As Anderson says, “The system forced

operators to fish in a manner that was

competitive, a race to catch a certain spe-

cies... and they used to throw away a lot

of fish. The fishers would keep the most

valuable fish and throw the others away.

Prohibited species catch limits typically

closed fisheries, not achievement of tar-

get species limits. It was also a difficult

balancing act because each year, quota

numbers would vary from species to spe-

cies.” Anderson acknowledges that Alas-

ka fishermen have traditionally been pro-

active in exercising particular care for the

environment, as has much of the state, but