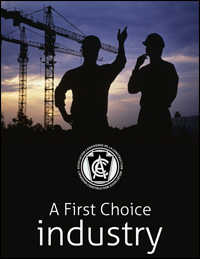

A first choice industry

The construction sector is a cornerstone of the Canadian economy. It employs approximately 7 per cent of Canada’s total workforce and is responsible for 6 per cent of Canada’s overall Gross Domestic Product – that’s 1.26 million workers and $90 billion in economic activity. The Canadian Construction Association (CCA) has represented that industry sector since 1918, giving voice to the goals of contractors, suppliers and allied business professionals. CCA represents more than 17,000 member firms and has over 70 local and provincial integrated partner associations, which means their industry voice is fairly loud.

The current focus for that voice is the issue of labour supply – more specifically, the upcoming lack of it.

The Construction Sector Council (CSC) is a trade labour market secretariat that releases an annual Labour Market Information (LMI) assessment. According to their LMI for 2011, the construction industry in Canada will have to find roughly 320,000 new workers by 2019 just to replace those that are retiring from the industry and keep pace with demand. As part of their assessment, the CSC examined how many of those jobs could be replaced domestically – as in, how many people are coming through the training system now, and how many current workers will be able to fill those jobs via labour mobility. After exhausting domestic sources, they concluded that approximately 157,000 workers will have to come from outside the country.

“Despite our best efforts to find those workers from the domestic pool in Canada, we still have to rely on immigration to fill those positions,†says Michael Atkinson, President of the CCA.

Canada’s current fertility rate is roughly 1.6 births per woman. Atkinson describes the international rule of thumb for replacing a country’s population as being a birth rate of 2.1. “Simple math shows that our needs in the labour market area are not dependent on the normal economic cycles,†he says. “This is not a temporary thing; this is something that we, among other industries in Canada, are facing because of our aging demographics, and because of our low fertility rate.â€

Because of that impending reliance on foreign labour sources, the CCA has been paying close attention to Canada’s current immigration systems, such as their Federal Skilled Worker and Temporary Foreign Worker programs. “We look at those and we say to ourselves ‘Well gee, you know, they are not exactly construction friendly,’†Atkinson says.

Getting with the program

The Federal Skilled Worker Program is the primary way a tradesperson or potential construction worker can immigrate to Canada to work – either of their own volition, or because they have been sponsored by a prospective employer. Under that program, an applicant needs to accrue 67 out of 100 points on a scoring system in order to be eligible. Unfortunately for the construction industry, the vast majority of those points are awarded for post secondary education or proficiency in either one of Canada’s official languages. “A lot of the tradespeople we’re looking for probably don’t have a postsecondary education,†Atkinson says. “They may have taken some formalised training if they have systems similar to our apprenticeship system, but chances are they won’t have postsecondary degrees. So they already fall behind the 8-ball in trying to amass those points.†On top of that, a lengthy queue has developed in that program, making for an arduous waiting game when it comes to bringing in foreign workers.

In response to these issues, the CCA has made submissions to Immigrations Canada. Their goals are to change the points system to make it more accessible for foreign tradespeople, and if the lag in the system is due to a lack of resources, they want the government to commit more. “They need to make sure we can build Canada’s future workforce – not just for our industry but for all the other industries in Canada that are facing the same challenges we are,†Atkinson says.

The other major facility by which CCA’s members have been accessing foreign workers is the Temporary Foreign Worker Program – and that also has some shortcomings the association would like to see addressed. At the moment, a Labour Market Opinion (LMO) is a required precondition to getting a temporary employee a VISA, and they are only issued to single employers. In construction, however, work can be seasonal or the employers that will be hiring have to first win competitive projects.

“In a particular region in the country you know whoever wins that contract is going to need the additional labour, but 12 to 18 months out you’re not sure if it’s going to be your firm,†Atkinson explains. “So we’ve been pushing for changes to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program that will allow these labour market opinions to be issued to more than one employer – let’s say to a group of employers in the same region, or all the competitors on a particularly large project that is coming down the pipe.â€

Overall, the immigration system was not set up to consider future labour requirements, and the CCA simply wants to see it become more proactive in that sense. “The kinds of reform that we’re looking for in the immigration system is trying to make it more responsive to the needs of the labour market – in our industry and many other industries as well,†Atkinson reiterates.

So far, the CCA has been encouraged with the recognition they have received from the government – the maximum number of immigrants under the Federal Skilled Worker program, for example, was recently announced to have increased, and Immigration Canada has already made some tentative changes to the point system. “It’s not all bleak,†Atkinson says. “I think the government understands our concerns and is attempting to work on them.â€

Not a last resort

Even more on the bright side, Atkinson says Canada has observed a growing change in the attitude of parents and high school guidance councillors in the last decade. Ten to 15 years ago, the labour supply issue may have had something to do with the potential stigma of working a construction job – these days, that stigma has long since disappeared. Today, Atkinson says, a college degree and a ticket in a particular trade is not a career of last resort, it is a career of first choice.

Recruitment efforts are strong at a grassroots level, and CCA have been actively making partnerships and launching initiatives to attract youth, as well as traditionally underutilised demographics such as women and First Nations people. The CCA website careersincivilconstruction.ca is one among many web tools and information the CCA and their local associations have provided. “All of our local construction associations have programs trying to encourage people to try and come into the construction industry and break all the myths down that it isn’t somebody with a hardhat, a pick and a shovel in a dirty ditch somewhere,†Atkinson says.

“The construction industry is extremely high tech,†he continues. “There’s new technology being used all the time, and it’s a career of first choice, not of last resort. It’s one of the last fields of endeavour where somebody truly can start on the tools at the bottom of the totem pole, then become their own boss and president of their own company through their experience in the industry.â€